KINDLING THE FIRES of CHANGE

Transcript from a talk given as part of the SRI/USR International Conference | 7 May 2020

(Two-part recording below)

(Two-part recording below)

Greetings friends

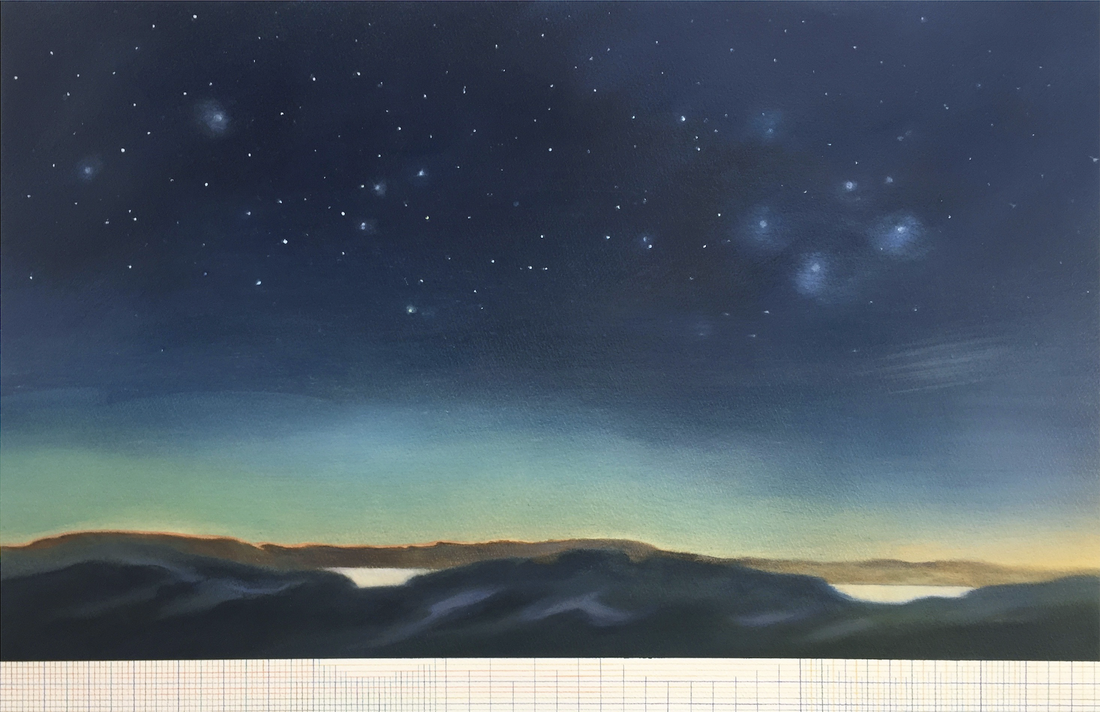

I’m joining you today from my studio on the Otago Peninsula, a thin strip of land surrounded by water on the lower East Coast of the South Island, New Zealand. My cottage is about a 30 minute drive from the centre of Dunedin, a small university city. It’s early morning here. 5.30AM. At this time of year - Autumn - 5.30AM means we’re at least 2 hours away from sunrise. So, I’m sitting here in the dark with you which feels rather apt, really, given we’re all somewhat ‘in the dark’ at this moment in our shared story.

We know that despite its discomforts, there can be deep beauty and revelatory opportunity in darkness. That we’re in a transition space with a potency and texture all its own.

It is said that without standing on a threshold for longer than is comfortable, we deny ourselves the experience of seeing beyond our old familiar stories, beyond all that we have become habituated to. That staying with the discomfort—really feeling into it—opens us to the wider, more inclusive world that lies in waiting before us.

I want to start by sharing a 2 minute clip from a video interview with Canadian choreographer Crystal Pite. In this vid., she speaks into the motivation behind her work ‘Flight Pattern’, a ballet set to Gorecki’s Symphony of Sorrowful Songs. The ballet is a moving exploration of the refugee crisis, from the plight of millions of displaced people to the fractures and dislocations that occur in our individual relationships.

This piece was first performed at London’s Royal Opera House in May 2019. I'm struck by the ways in which it speaks into the situation we’re in today with the global Covid-19 crisis—its strange liminality and limbo, the altered parameters of our social interactions and prescribed communal behaviours. . . Many we know speak of feeling like hostages in their own homes and of being able to identify for the first time with those who have experienced the stresses of long-term incarceration, hospitalisation, deprivation and marginalization of every description…

I invite you to watch closely the dancer’s bodies…

I’m joining you today from my studio on the Otago Peninsula, a thin strip of land surrounded by water on the lower East Coast of the South Island, New Zealand. My cottage is about a 30 minute drive from the centre of Dunedin, a small university city. It’s early morning here. 5.30AM. At this time of year - Autumn - 5.30AM means we’re at least 2 hours away from sunrise. So, I’m sitting here in the dark with you which feels rather apt, really, given we’re all somewhat ‘in the dark’ at this moment in our shared story.

We know that despite its discomforts, there can be deep beauty and revelatory opportunity in darkness. That we’re in a transition space with a potency and texture all its own.

It is said that without standing on a threshold for longer than is comfortable, we deny ourselves the experience of seeing beyond our old familiar stories, beyond all that we have become habituated to. That staying with the discomfort—really feeling into it—opens us to the wider, more inclusive world that lies in waiting before us.

I want to start by sharing a 2 minute clip from a video interview with Canadian choreographer Crystal Pite. In this vid., she speaks into the motivation behind her work ‘Flight Pattern’, a ballet set to Gorecki’s Symphony of Sorrowful Songs. The ballet is a moving exploration of the refugee crisis, from the plight of millions of displaced people to the fractures and dislocations that occur in our individual relationships.

This piece was first performed at London’s Royal Opera House in May 2019. I'm struck by the ways in which it speaks into the situation we’re in today with the global Covid-19 crisis—its strange liminality and limbo, the altered parameters of our social interactions and prescribed communal behaviours. . . Many we know speak of feeling like hostages in their own homes and of being able to identify for the first time with those who have experienced the stresses of long-term incarceration, hospitalisation, deprivation and marginalization of every description…

I invite you to watch closely the dancer’s bodies…

Crystal Pite spoke in these few minutes of wanting to ‘evoke a stage in the journey’ of this community ‘in flight’, to say something about the limbo state of these refugees that has to do with having left a situation—an impossible situation—and to not yet have entered the next phase of life. To be in between. So the past is still clinging; there are flashbacks, memories, wonderings and regrets and yet the future is no more than a blurred horizon, unformed and uncertain. She imagined what it must be like to ‘come up against a border, a holding area, a waiting room… a check-point or camp. To be held there, unable to move either forward or back.'

She speaks of her work as ‘a way of coping with the world, a way of managing the emotions and the thoughts that arise in crisis situations.’ And when asked if she thinks Art has the ability to effect change, she replies,

‘It’s a question I ask myself daily. I don’t expect it to. What I want is that we come together in the theatre. And that we have an opportunity to open up channels to the Humane and to each other. Whether or not the work actually effects change, I don’t know…”

She concedes she often feels inadequate, overwhelmed, powerless, frustrated and angry. She wonders if her creative pursuits are the best use of her time, if it’s the best way she can offer something to the situation. She admits to struggling with those thoughts and questions 'a lot' and yet, she also knows that if she’s going to attempt to talk about something that’s so important to her and that touches her deeply, then ‘it had better be through dance’, since dance is her first language and therefore the best hope she has of speaking clearly and truthfully about the things she feels moved by, whether directly or indirectly.

She speaks of her work as ‘a way of coping with the world, a way of managing the emotions and the thoughts that arise in crisis situations.’ And when asked if she thinks Art has the ability to effect change, she replies,

‘It’s a question I ask myself daily. I don’t expect it to. What I want is that we come together in the theatre. And that we have an opportunity to open up channels to the Humane and to each other. Whether or not the work actually effects change, I don’t know…”

She concedes she often feels inadequate, overwhelmed, powerless, frustrated and angry. She wonders if her creative pursuits are the best use of her time, if it’s the best way she can offer something to the situation. She admits to struggling with those thoughts and questions 'a lot' and yet, she also knows that if she’s going to attempt to talk about something that’s so important to her and that touches her deeply, then ‘it had better be through dance’, since dance is her first language and therefore the best hope she has of speaking clearly and truthfully about the things she feels moved by, whether directly or indirectly.

The reasons I chose to share this short piece today are, I imagine, plain to see. I feel similarly about painting and poetry—namely, that they are my ‘best hope’ of speaking clearly and truthfully about the things I am moved by.

I admit to going through something of a dilemma around how best to shape our time together this morning. In our top-heavy, head-centric world, a big part of me wanted not to fill the space with words—or even with images—and instead to suggest we all take a deep, s l o w breath and feel into what poet Mary Oliver* refers to as our ‘soft animal bodies’. Each of us carries within us a wealth of stories - and I love first and foremost to listen. So I was more than a little tempted to suggest we kick off our shoes, pull up our stools, gather barefoot around the campfire and pass a talking stick around the circle. Or simply sit together and allow the silence to speak to us.

There’s something primal and intimate about sitting quietly together in the dark and watching the flames dance. Like a return to innocence and animal alertness.

My hope is that, in spite of my going ahead with words, we experience something of this ‘return’ during our brief time together today.

I admit to going through something of a dilemma around how best to shape our time together this morning. In our top-heavy, head-centric world, a big part of me wanted not to fill the space with words—or even with images—and instead to suggest we all take a deep, s l o w breath and feel into what poet Mary Oliver* refers to as our ‘soft animal bodies’. Each of us carries within us a wealth of stories - and I love first and foremost to listen. So I was more than a little tempted to suggest we kick off our shoes, pull up our stools, gather barefoot around the campfire and pass a talking stick around the circle. Or simply sit together and allow the silence to speak to us.

There’s something primal and intimate about sitting quietly together in the dark and watching the flames dance. Like a return to innocence and animal alertness.

My hope is that, in spite of my going ahead with words, we experience something of this ‘return’ during our brief time together today.

*

I recently learnt a new word. An Inuit word that came to me via Bayo Akomolafe*. The word is qarttsiluni. More than a word, it’s an invitation and an invocation. It translates to ‘Sitting together in the darkness’ and tells the story of tribal elders who travel away from their homes and familiar territory and enter a retreat space where they sit together, waiting in the dark for a new song to rise. My understanding is that this song is both for and from the whales who in turn gift that song on to the sea and to all living creatures.

Song as a current—and currency—of hope in dark times.

Song as a current—and currency—of hope in dark times.

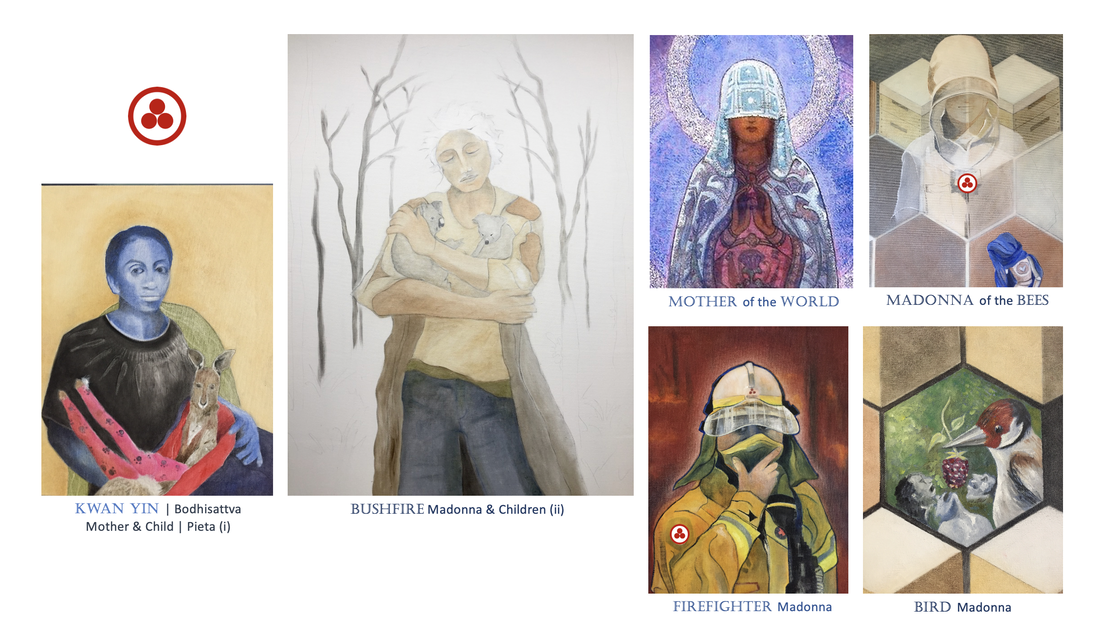

Some of you may be familiar with a series of canvases I’ve been working on for some years now – I shared the first of these (the one you see here) at the last conference I attended in person in Phoenix. A honeycomb journal, they use the architecture of the bee as a framework; each hexagonal chamber contains an image that expands into a story that also relates to the stories on either side of it.

These honeycomb paintings are a way for me to engage the themes and happenings of our times—a means of bringing them to light and of bringing light to them. Anchor-points are, of course, an illusion, for nothing can be fixed into place for long, but these paintings are a place I go to in order to try and make sense of the world, a place to recover what's lost or to document what moves me on any given day—the stories that land in these chambers are inevitably far-ranging; the birth of a grandchild, the loss of someone dear; the Mosque shootings in Christchurch, the discovery of a new star; an incident that exposes human frailty, cruelty or courage, an astronomical or scientific breakthrough, the raw effects of climate change…

These honeycomb paintings are a way for me to engage the themes and happenings of our times—a means of bringing them to light and of bringing light to them. Anchor-points are, of course, an illusion, for nothing can be fixed into place for long, but these paintings are a place I go to in order to try and make sense of the world, a place to recover what's lost or to document what moves me on any given day—the stories that land in these chambers are inevitably far-ranging; the birth of a grandchild, the loss of someone dear; the Mosque shootings in Christchurch, the discovery of a new star; an incident that exposes human frailty, cruelty or courage, an astronomical or scientific breakthrough, the raw effects of climate change…

This image shows the journal I’m working on currently. This honeycomb has 121 chambers and was prompted by two months travel-time in Italy last year. The decorative elements in this painting are borrowed from sidewalks and sacred spaces including those of the Duomo in Siena and the basilica of St. Francis in Assisi. There are hints at things observed whilst walking with friends in ancient grottos and through stony olive groves; one of these chambers is occupied by a man encountered in the Academia Gallery in Venice. Hieronymus Bosch had painted him into one of his triptychs; he's forever captured now in deep conversation with a bird.

This honeycomb also contains images of the Amazonian fires and multiple refugee boat crossings; in the lower right hand corner, you will notice a Korean Comfort Woman; the small devic being who keeps her company is holding up an apple above her right shoulder, assuring her she is not alone.

This honeycomb also contains images of the Amazonian fires and multiple refugee boat crossings; in the lower right hand corner, you will notice a Korean Comfort Woman; the small devic being who keeps her company is holding up an apple above her right shoulder, assuring her she is not alone.

It’s difficult to comprehend the devastating bushfires that swept across parts of New South Wales and North-Eastern Victoria, Australia occurred just a few short months ago. So much has happened and been tipped on its head since then…

Images of these fires and the overwhelming suffering of billions of animals, birds and plants were published daily online. Many of you will have ‘met’ Toni and Lewis, seen film footage of Toni pulling off her top and running headlong into the forest to rescue this terrified koala bear from the flames.

During this year’s especially catastrophic bushfire season, I was drawn away from my Honeycomb canvas and into making a series of paintings as tributes to the first responders and to the animals who lost their lives in those fires. At times like these, I turn always to my garden and studio—to the process of engagement-through-making. Wherever possible I call the affected people, animals and places by name. This provides way of a moving from the realms of remote, abstract news reportage to more personal, heart-opening connection.

‘If I look at the masses, I will never act. If I look at the one, I will.’ *

The paintings in the next two slides are from a series of Firefighter Madonnas, each of them a Bodhisattva, a Goddess of Compassion and Warrior Woman offering strength and comfort to animals and to the marginalized and vulnerable, as a mother does to her child.

These paintings are unfinished, a glimpse into my studio where various works in this series are in process. I’m more concerned these days with capturing and communicating a moment in our interrelated story, seeking connection with subjects that turn up to open the 'channels to the Humane’ we heard Chrystal Pite speaking of earlier. This 'making' space opens a way into sometimes tricky questions and discomforting conversations (let that be reason enough to engage with them).

In our head-heavy, information-driven world it feels essential that for change to happen on any level, we allow ourselves to have embodied responses to what’s happening in and around us. News reportage is incessant, noisy and very often conflicted. How do we hold a steady position as empathic and discriminating observers? How effective are we when it comes to fostering honest, safe and meaningful exchange as we weave ourselves and our diverse stories together?

Images of these fires and the overwhelming suffering of billions of animals, birds and plants were published daily online. Many of you will have ‘met’ Toni and Lewis, seen film footage of Toni pulling off her top and running headlong into the forest to rescue this terrified koala bear from the flames.

During this year’s especially catastrophic bushfire season, I was drawn away from my Honeycomb canvas and into making a series of paintings as tributes to the first responders and to the animals who lost their lives in those fires. At times like these, I turn always to my garden and studio—to the process of engagement-through-making. Wherever possible I call the affected people, animals and places by name. This provides way of a moving from the realms of remote, abstract news reportage to more personal, heart-opening connection.

‘If I look at the masses, I will never act. If I look at the one, I will.’ *

The paintings in the next two slides are from a series of Firefighter Madonnas, each of them a Bodhisattva, a Goddess of Compassion and Warrior Woman offering strength and comfort to animals and to the marginalized and vulnerable, as a mother does to her child.

These paintings are unfinished, a glimpse into my studio where various works in this series are in process. I’m more concerned these days with capturing and communicating a moment in our interrelated story, seeking connection with subjects that turn up to open the 'channels to the Humane’ we heard Chrystal Pite speaking of earlier. This 'making' space opens a way into sometimes tricky questions and discomforting conversations (let that be reason enough to engage with them).

In our head-heavy, information-driven world it feels essential that for change to happen on any level, we allow ourselves to have embodied responses to what’s happening in and around us. News reportage is incessant, noisy and very often conflicted. How do we hold a steady position as empathic and discriminating observers? How effective are we when it comes to fostering honest, safe and meaningful exchange as we weave ourselves and our diverse stories together?

In the first of the canvases in this slide, the Mother takes the form of Kwan Yin, a blue Bodhisattva. In a pose loosely reminiscent of the many pietas that have been painted down the years, she’s wearing a plain black T-shirt; in her arms she cradles a baby kangaroo, rescued from the fires and bound in a bright pink body cast.

In another of the paintings the Mother principle expresses through a bird. Recognizing how disconnected our species has become from Nature (and, too, our Soul Nature/our inherent divinity), she offers fruit to hungry Humanity, knowing that one of the ways back to a life that is nourishing, sustaining and meaningful is via relationship with our Natural world.

I’ve been looking to the many archetypal Mothers who have come through to us over the years – there’s a rich archive of stories, mythology, spiritual traditions and art history to learn from.

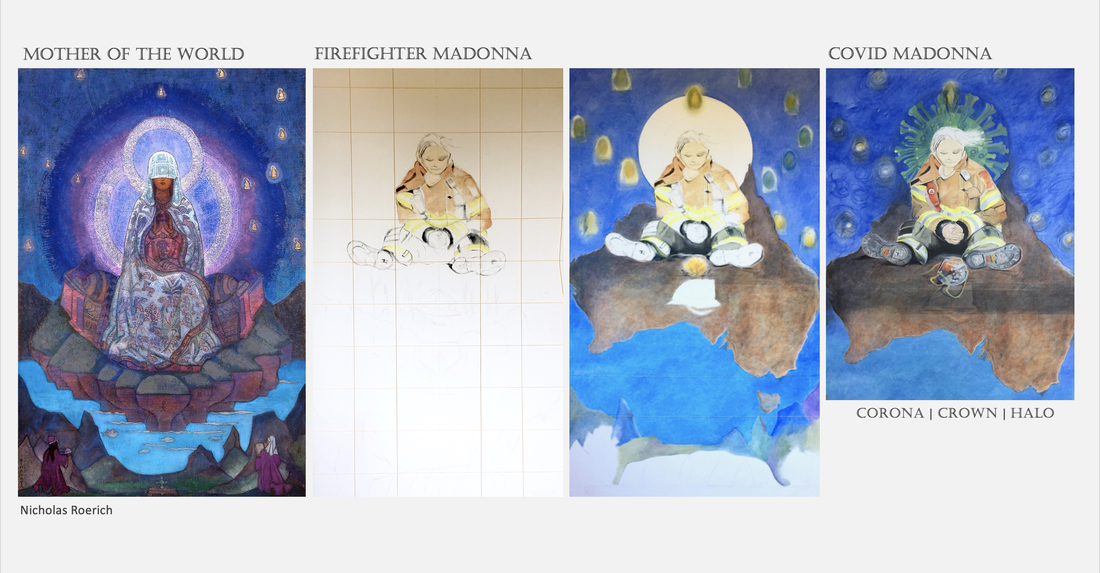

Most of us will be familiar with Nicholas Roerich’s iconic painting ‘The Mother of the World’ (a detail of which is shown on the right of this slide). I have often been struck by her composure and by the hooded veil that shields her eyes—as if she’s looking inward, holding a space of meditative poise that suggests a deep attunement to the state of the world. She is calm, embodied, undistracted.

In another of the paintings the Mother principle expresses through a bird. Recognizing how disconnected our species has become from Nature (and, too, our Soul Nature/our inherent divinity), she offers fruit to hungry Humanity, knowing that one of the ways back to a life that is nourishing, sustaining and meaningful is via relationship with our Natural world.

I’ve been looking to the many archetypal Mothers who have come through to us over the years – there’s a rich archive of stories, mythology, spiritual traditions and art history to learn from.

Most of us will be familiar with Nicholas Roerich’s iconic painting ‘The Mother of the World’ (a detail of which is shown on the right of this slide). I have often been struck by her composure and by the hooded veil that shields her eyes—as if she’s looking inward, holding a space of meditative poise that suggests a deep attunement to the state of the world. She is calm, embodied, undistracted.

During the time of the Australian, Californian and Amazonian fires (a time when much of the world was, quite literally, 'on fire'), Roerich’s Mother of the World painting came to mean a great deal to me. The veil the artist gave her took on the elements of a ‘helmet’ and I started seeing her everywhere – in the women on the front lines of disaster zones, in refugee camps and hospital Emergency Departments; she turned up wielding firefighting hoses, delivering food supplies and emergency medical equipment. The badge she wore either on her sleeve or on her breast pocket was not that of the local government Department but The Banner of Peace.

She expressed as a teacher, a beekeeper, a homeless woman in India; I met her again in my daughter, in the delicate hooded mushrooms in my garden and in my 2-year granddaughter doing dress-ups on Waiheke Island.

She expressed as a teacher, a beekeeper, a homeless woman in India; I met her again in my daughter, in the delicate hooded mushrooms in my garden and in my 2-year granddaughter doing dress-ups on Waiheke Island.

And then, it was as if we all woke up one morning to find the music we’d been listening to—as well as the frenetic soundtrack we’d all become accustomed to—had stopped.

Into the frame came this sinister yet strangely beautiful shape with a seductive name. Coronavirus. Quickly adjusted to Covid-19. Or C-19.

Rest is possibly the least-acknowledged of the 4th Ray energies—we tend to think of the 4th Ray first as a Ray of War, or of Harmony through Conflict—and of the Arts expressing most strongly through the 4th and 7th Rays. The 4th Ray is also associated with the Base Chakra and the Adrenals, and with the energies of grounding, purification and Rest.

For some reason rest has become under-sung, not only as an aspect of the 4th Ray, but as an essential key to overall well-being and vitality. Is it not rest that supports and enables sustained efficacy of effort in any, if not all, our human endeavours? Without rest, our bodies and brains cannot adequately replenish and we run the risk of burn-out.

Just as a loaf of bread requires time to rest so that the yeast can prove and the dough rise, seeds and soil need fallow time in order to germinate and regenerate. Creative ideas, too, require regular and unhurried incubation periods. In our clamorous world we need spaces to settle, times of simple being and receptivity.

How else can we hope to hear the new song?

And have you noticed that the PAUSE symbol in music notation is half that of the symbol for the Sun and the Monad? Perhaps there’s a message in there for us?

For some reason rest has become under-sung, not only as an aspect of the 4th Ray, but as an essential key to overall well-being and vitality. Is it not rest that supports and enables sustained efficacy of effort in any, if not all, our human endeavours? Without rest, our bodies and brains cannot adequately replenish and we run the risk of burn-out.

Just as a loaf of bread requires time to rest so that the yeast can prove and the dough rise, seeds and soil need fallow time in order to germinate and regenerate. Creative ideas, too, require regular and unhurried incubation periods. In our clamorous world we need spaces to settle, times of simple being and receptivity.

How else can we hope to hear the new song?

And have you noticed that the PAUSE symbol in music notation is half that of the symbol for the Sun and the Monad? Perhaps there’s a message in there for us?

In late February, I began a new ‘to-scale’ canvas prompted by Nicholas Roerich’s Mother of the World painting (seen here on the left). I’d caught a glimpse of a female firefighter sitting in front of her fire truck at the end of yet another marathon day. She was surrounded by the tools of her trade – a torch, her mobile phone, a hand-held radio. Her helmet with its clear visor lay on its side between her feet. She looked deeply weary. Contemplative, too.

I wanted very much to paint her.

I laid down the grounds for a canvas that would, I thought, include an overt reference to the Australian continent and otherwise draw in various elements from Roerich’s painting, specifically the Mother’s halo, the floating Buddhas in the upper hemisphere and the small figures on either side of an altar in the lower fifth of his composition.

About two weeks into the Covid-19 lockdown period, I found myself stalling with this painting, then grinding to a complete standstill.

I wanted very much to paint her.

I laid down the grounds for a canvas that would, I thought, include an overt reference to the Australian continent and otherwise draw in various elements from Roerich’s painting, specifically the Mother’s halo, the floating Buddhas in the upper hemisphere and the small figures on either side of an altar in the lower fifth of his composition.

About two weeks into the Covid-19 lockdown period, I found myself stalling with this painting, then grinding to a complete standstill.

In the mornings—as has long been my rhythm—I’d walk into my studio intending to pick up my brushes and carry on from where I’d left off the day before.

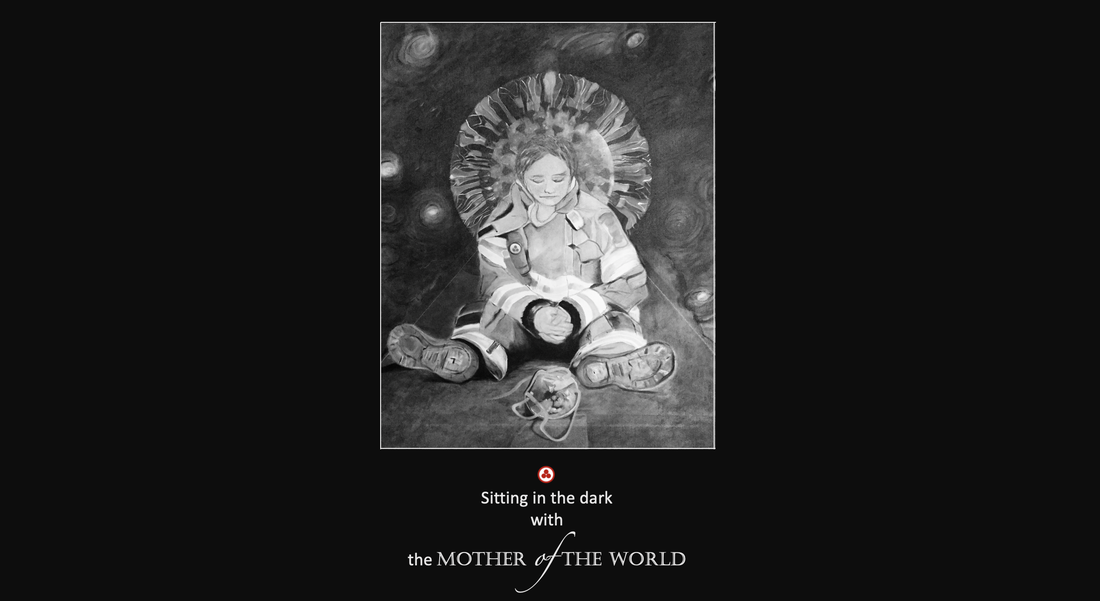

My firefighter would be there, sitting exactly as I’d left her the day before, eyes lowered as if she was looking inward or perhaps at the ground in front of her. I took to setting down my brushes, pulling up my chair and sitting a while with her. I recognized that not only was her exhaustion my exhaustion, it was our collective exhaustion. And it was Mother Earth’s frayed nervous system expressing, too--

How long our planet has borne the relentless press of industry on her chest*.

I found myself wanting to help her out of her firefighter’s uniform, to peel off her heavy steel-toed boots so her feet could breathe. To dress her in something lighter.

She wouldn't have a bar of it.

Later that same day, during a television news report addressing the spread of the COVID virus, I noticed that first responders in New Jersey and New York city were dressed in the very same standard-issue uniform as the one my firefighter was wearing. I stopped wanting to change her, decided to leave her the way she was.

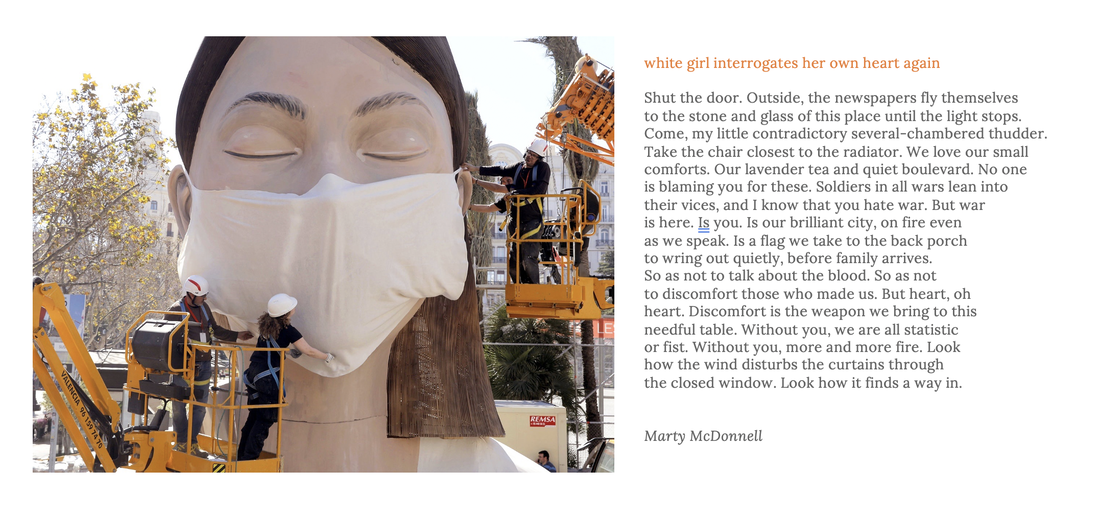

The helmet at her feet merged with the ground, made way for a face mask. One morning I gave her a haircut. Short hair would be easier to manage during her long hours of duty.

The halo behind her firefighter’s head sprouted corona-type spikes. Around these, the suggestion of trees, with life-line limbs reaching into the ethers, a phalanx of protection that coiled loosely through and around the Madonna’s hair and her new COVID crown.

We sat together a lot during those early lockdown days.

I turned a raft of questions around, visited strange states and places in myself. I was beset with concerns about the ways in which each of us is having an entirely different experience of self-isolation; that the solitude I value and protect as essential to my nature would feel like a prison-, or worse, a death-sentence to a neighbour, a battered woman living a few streets along from me with her violent, now unemployed, partner-- both of them barred access to their usual systems of support.

What are the ways in which we inadvertently exclude others? What do we shutter ourselves from because to do otherwise would be difficult, inconvenient or discomforting?

My firefighter would be there, sitting exactly as I’d left her the day before, eyes lowered as if she was looking inward or perhaps at the ground in front of her. I took to setting down my brushes, pulling up my chair and sitting a while with her. I recognized that not only was her exhaustion my exhaustion, it was our collective exhaustion. And it was Mother Earth’s frayed nervous system expressing, too--

How long our planet has borne the relentless press of industry on her chest*.

I found myself wanting to help her out of her firefighter’s uniform, to peel off her heavy steel-toed boots so her feet could breathe. To dress her in something lighter.

She wouldn't have a bar of it.

Later that same day, during a television news report addressing the spread of the COVID virus, I noticed that first responders in New Jersey and New York city were dressed in the very same standard-issue uniform as the one my firefighter was wearing. I stopped wanting to change her, decided to leave her the way she was.

The helmet at her feet merged with the ground, made way for a face mask. One morning I gave her a haircut. Short hair would be easier to manage during her long hours of duty.

The halo behind her firefighter’s head sprouted corona-type spikes. Around these, the suggestion of trees, with life-line limbs reaching into the ethers, a phalanx of protection that coiled loosely through and around the Madonna’s hair and her new COVID crown.

We sat together a lot during those early lockdown days.

I turned a raft of questions around, visited strange states and places in myself. I was beset with concerns about the ways in which each of us is having an entirely different experience of self-isolation; that the solitude I value and protect as essential to my nature would feel like a prison-, or worse, a death-sentence to a neighbour, a battered woman living a few streets along from me with her violent, now unemployed, partner-- both of them barred access to their usual systems of support.

What are the ways in which we inadvertently exclude others? What do we shutter ourselves from because to do otherwise would be difficult, inconvenient or discomforting?

These words from poet Maya Angelou; “We need the courage to create ourselves daily, to be bodacious enough to create ourselves daily — as Christians, as Jews, as Muslims, as thinking, caring, laughing, loving human beings. I think that the courage to confront evil and turn it by dint of will into something applicable to the development of our evolution, individually and collectively, is exciting, honorable.”

|

We wear the mask that grins and lies,

It shades our cheeks and hides our eyes,-- This debt we pay to human guile; With torn and bleeding hearts we smile, And mouth with myriad subtleties. Why should the world be over-wise, In counting all our tears and sighs? Nay, let them only see us, while We wear the mask. We smile, but O great Christ, our cries To thee from tortured souls arise. We sing, but oh, the clay is vile Beneath our feet, and long the mile; But let the world think otherwise, We wear the mask!* |

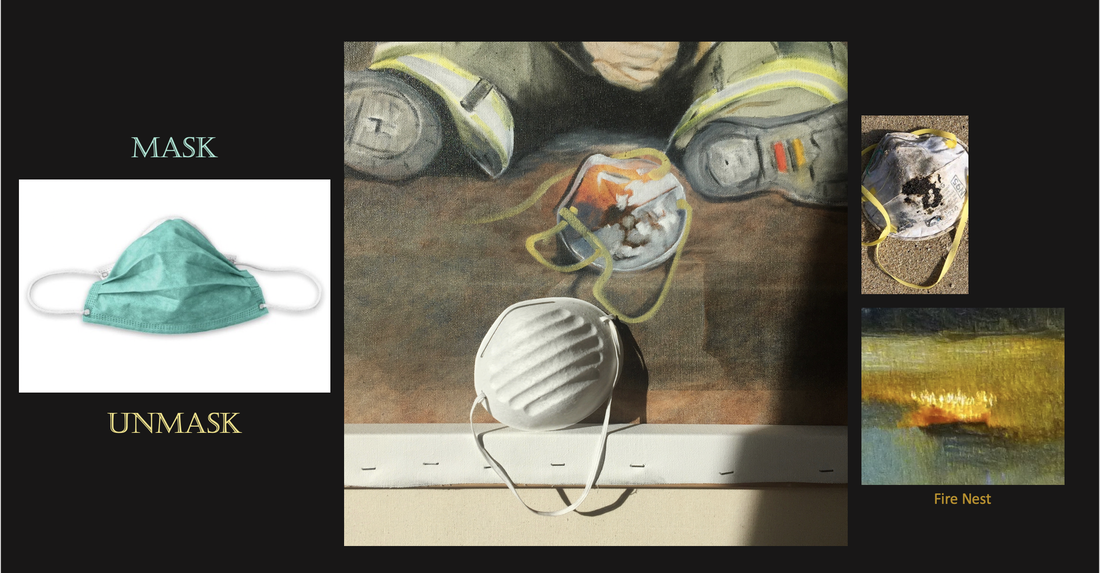

Looking more closely at this firefighter’s helmet-turned-mask, I noticed that inside it was a fire nest, small sparks safely contained and flickering with questions. And I was reminded of two stories I’d been told about fires that had left their deep, and comforting, imprint on my being.

The first was Mac Macartney’s* retelling of a traditional North American Indian story, The Children’s Fire:

A group of elders were sitting together in counsel in the heart of a forest. They had long been pondering how best to govern their people and serve their community. After a time, it came to one of them that at the beginning of every council meeting, a fire should be lit. And the fire was to be dedicated to the children of the tribe and be referred to as The Children’s Fire. Any decisions made or laws passed would have to pass a test, ‘Will this bring harm to the children?” And then, ‘Will this decision bring harm to our children’s children? Or to their children’s children - for seven generations hence?”

And when they spoke of the children they were not speaking only of the human children but also of the animal’s children and the bird’s children, and the children of the insects and reptiles and those of the plant and mineral kingdoms. No decision should ever be made or law passed unless it promised never to harm the children…

The second story that the Madonna’s fire nest reminded me of was one I read many years ago as spun by an artist friend in the UK, Jane Adams*. I’ve since forgotten which of these words are hers and which are mine; they’ve merged into one quasi-poem or word image— I thank her for them, and for much else besides…

|

'In days gone by, people carried fire nests

from hearth to hearth, a spark wrapped in grass, some slow-burning material— ignited by air, gentle breath, lungs the alchemist’s bellows. Today we have matches and lighters— we forget the magic, the tenderness of embers passing from person to person and place to place.” |

I took to spending time each day sitting with the Madonna you see now on your screen. She drew me into a process of self-enquiry that asked for my full attention.

What might this coronavirus be revealing to us? To me? What new ways of being or perceiving was it asking us to consider? And how was I doing with the blind spots of my privilege? What monsters of my shadow nature might it be exposing? What angels?

The questions kept coming. Could I expand my appetite for joy, knowing I must also enter, re-enter and enter again, ‘the sorrow garden’*?

What of laughter? Can you laugh more readily, she asked. Open more to wonder and surprise?

And what of your fears? How at ease are you with the inevitability of dying and death – your own and that of those you love? You speak convincingly of death as a birthing into the next realm but how comfortable are you with that notion – really? Where are you stuck? Intolerant? Inflexible? Habituated? Conditioned? Not living in alignment with your true nature? And what are the things you use as your ‘obstacles of convenience’?

Bayo Akomolafe* wrote an essay on school education systems that borrows its title from a Zen saying, ‘Name the colour. Blind the eyes.’ And I heard a related statement in a short film I watched just yesterday titled ‘The Music of the Spheres’. When asked how she could work without sight in her chosen scientific field, blind Puerto-Rican astrophysicist Wanda Diaz-Merced said, ‘If we see only with our eyes, our perception is very narrow.’

This is not a time to be looking to anything known, familiar or fixed, the Madonna in my painting insisted. So-called 'answers' are only ever temporary anyway. This is a time for letting go of all the old nonsense, a releasing of our grip on stale, fixed stories and surrendering instead into the unknown—that deep, dark space where the new songs are shuddering into being.

I recall Pope Francis making a decision at the beginning of his papal term choosing to ‘leave the Vatican’, to live in quarters closer in every way possible to the community he serves. At the time, I made a note to myself, What are my private Vaticans? The comfort zones I occupy through habit, privilege, fear?

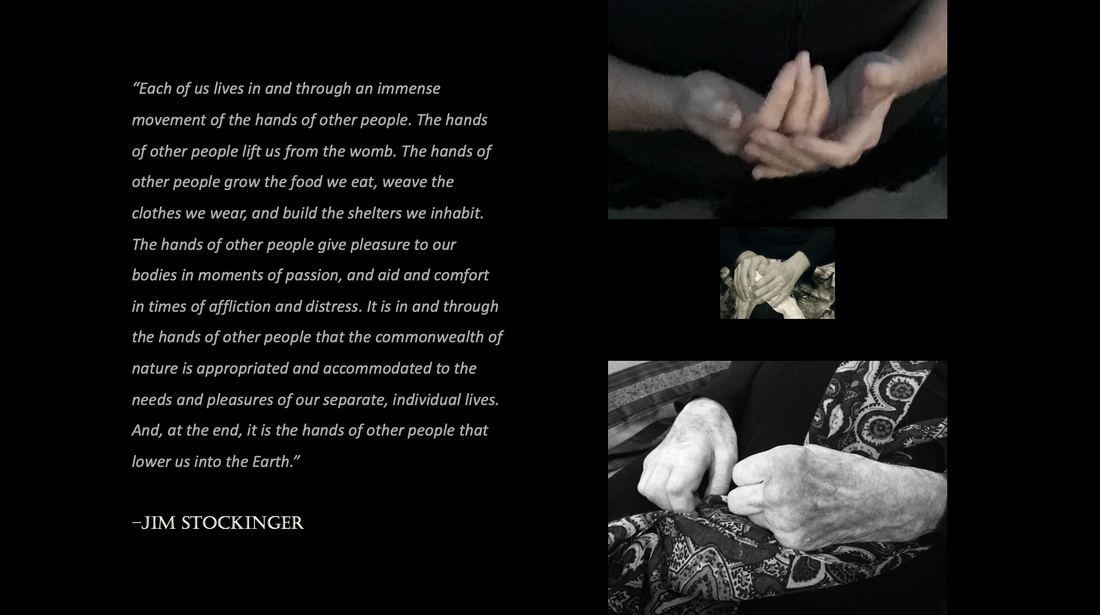

In an article posted online earlier this week, peace ambassador Miki Kashtan* entered the difficult territory of economic inequities – those so glaringly in evidence before this pandemic and those that have been further exposed by it. She quoted Jim Stockinger.

Philip Shepherd* whose books and embodiment work I value greatly, said during a Livestream talk on Facebook last week,

“Humanity is suffering and locked down; meantime Nature is probably doing better than She’s done in decades. . . It’s interesting to look at the hierarchies of Nature—so what’s more important? A tree? Worms? Clouds? Or fungi? It’s an absurd question! What’s more important? Every one of them supports and upholds the other. Nature is this matrix of harmonizing and play and creativity.'

“Humanity is suffering and locked down; meantime Nature is probably doing better than She’s done in decades. . . It’s interesting to look at the hierarchies of Nature—so what’s more important? A tree? Worms? Clouds? Or fungi? It’s an absurd question! What’s more important? Every one of them supports and upholds the other. Nature is this matrix of harmonizing and play and creativity.'

He went on to say, "Apply this same question to human society—what’s more important? The CEOs, the bakers or the cleaners?

Again, it’s an absurd question.

The masks we’ve been instructed to wear during this time – the mask that's lying as an object of contemplation between my COVID Madonna’s feet—are an opportunity for us to unmask so many of the things we’ve become blindly identified with or that we’ve avoided engaging with altogether.

Poet LaoTzu wrote--

Men are born soft and supple; dead they are stiff and hard.

Plants are born tender and pliant; dead, they are brittle and dry.

Thus whoever is stiff and inflexible is a disciple of death.

Whoever is soft and yielding is a disciple of life.

“COVID is delivering a different perspective on all our traditional frameworks. We humans have a hierarchy of values that does not exist anywhere in Nature”, says Philip Shepherd*, “and we’ve wanted everything to fit within the constraints of those values…” Come hell or high water. Mercifully, the web of interrelationships that Nature recognizes and thrives by is being revealed to us again, reminding us of core principles we have (in)conveniently forgotten.

We are going to continue to see significant disruption and suffering in the coming days, weeks, months and years as our already-failing economies collapse and unemployment soars. The impact will once again be most palpably felt by the marginalised. Much of this fall-out has been a long time coming. We've known this, yet turned a blind eye. What if, instead of our compulsive focus on consumption and ownership, we were to apply ourselves instead to a Review of Service? The Circulation of Gifts. Contracts of Care that are pliable and alive and informed by the rising sap of each new moment?

We belong intimately to each other and to our living, breathing world.

Again, it’s an absurd question.

The masks we’ve been instructed to wear during this time – the mask that's lying as an object of contemplation between my COVID Madonna’s feet—are an opportunity for us to unmask so many of the things we’ve become blindly identified with or that we’ve avoided engaging with altogether.

Poet LaoTzu wrote--

Men are born soft and supple; dead they are stiff and hard.

Plants are born tender and pliant; dead, they are brittle and dry.

Thus whoever is stiff and inflexible is a disciple of death.

Whoever is soft and yielding is a disciple of life.

“COVID is delivering a different perspective on all our traditional frameworks. We humans have a hierarchy of values that does not exist anywhere in Nature”, says Philip Shepherd*, “and we’ve wanted everything to fit within the constraints of those values…” Come hell or high water. Mercifully, the web of interrelationships that Nature recognizes and thrives by is being revealed to us again, reminding us of core principles we have (in)conveniently forgotten.

We are going to continue to see significant disruption and suffering in the coming days, weeks, months and years as our already-failing economies collapse and unemployment soars. The impact will once again be most palpably felt by the marginalised. Much of this fall-out has been a long time coming. We've known this, yet turned a blind eye. What if, instead of our compulsive focus on consumption and ownership, we were to apply ourselves instead to a Review of Service? The Circulation of Gifts. Contracts of Care that are pliable and alive and informed by the rising sap of each new moment?

We belong intimately to each other and to our living, breathing world.

Among the sensory pleasures of my lockdown time have been walks and cycles around our peninsula; gardening (a fair bit of digging and heavy earth-moving!) and mushroom hunting; activities that have taken me back to the rhythms of my childhood in Africa, a time before our world became the runaway train it is today.

As a child I pretty much lived outdoors, blissfully and intimately attuned to the cycles and rhythms of nature. My sibs and I wandered the veldt barefoot, experienced the textures and temperament of the land through our feet, our skin, our six senses. Our vocabulary included a deeply felt experience of the earth by day and the starlit sky by night—it was the language of falling stars and comets, bark and berries, thorns, dirt and stones; the companionship of spiders, snakes, flying ants, birds and palm-sized Molly moths.

We attended Sunday School, read the bible, learned the intricacies of Christian doctrine and at the same time battled the contradictory cruelties of the Apartheid system. Alongside stories about Rupert Bear and Pookie Rabbit were parables about Jesus, the Pharisees and the Good Samaritan. I'd sit on the sun-warmed kitchen steps of our Johannesburg home shelling peas with Sophie, an ample-bosomed Xhosa woman with a happy-gap between her two front teeth, and - at the height of summer - would harvest elaborately striped mopani worms from a trumpet vine with the kindest Malawian man named Wilned. Story-tellers both, these patient, gentle people introduced me to the tales of Africa; the thrilling (and slightly terrifying) lore of sangomas (witch doctors) and their indigenous practices; medicine spells, chanting and bone-throwing, the compelling allure of magic. They assured me ancestors returned to earth after death, that they inhabited the bodies of lizards, tortoises and turtle doves. If I looked deeply into the eyes of animals, I might see beyond this time to a place where men and women of old were no longer tethered to Earth but drifting, and at home, amongst the stars.

The subtle realms leaned in close.

As a child I pretty much lived outdoors, blissfully and intimately attuned to the cycles and rhythms of nature. My sibs and I wandered the veldt barefoot, experienced the textures and temperament of the land through our feet, our skin, our six senses. Our vocabulary included a deeply felt experience of the earth by day and the starlit sky by night—it was the language of falling stars and comets, bark and berries, thorns, dirt and stones; the companionship of spiders, snakes, flying ants, birds and palm-sized Molly moths.

We attended Sunday School, read the bible, learned the intricacies of Christian doctrine and at the same time battled the contradictory cruelties of the Apartheid system. Alongside stories about Rupert Bear and Pookie Rabbit were parables about Jesus, the Pharisees and the Good Samaritan. I'd sit on the sun-warmed kitchen steps of our Johannesburg home shelling peas with Sophie, an ample-bosomed Xhosa woman with a happy-gap between her two front teeth, and - at the height of summer - would harvest elaborately striped mopani worms from a trumpet vine with the kindest Malawian man named Wilned. Story-tellers both, these patient, gentle people introduced me to the tales of Africa; the thrilling (and slightly terrifying) lore of sangomas (witch doctors) and their indigenous practices; medicine spells, chanting and bone-throwing, the compelling allure of magic. They assured me ancestors returned to earth after death, that they inhabited the bodies of lizards, tortoises and turtle doves. If I looked deeply into the eyes of animals, I might see beyond this time to a place where men and women of old were no longer tethered to Earth but drifting, and at home, amongst the stars.

The subtle realms leaned in close.

We forget sometimes that turning over the compost is as rich and sacred a process as is seeking to deepen our intellectual and esoteric understandings.

My children’s father used to sing the praises of human bodies as ‘hosts to microbial zoos’ without which we could fulfil neither the most basic, nor the most elevated, of our earthly functions and service.

And did you know that human excrement, when mixed with sawdust—a gift from a lovingly pruned tree—becomes the most nutrient-rich compost for fruit trees and roses?

During this lockdown period, while I feel I haven't ‘accomplished’ much in any outwardly measurable sense, I do feel I’ve been recovering some of the 'innate comprehension' I had as a very young child and that for reasons both valid and invalid, I'd allowed myself to become separated from. I’ve appreciated connecting again with the deep blessing of those early childhood experiences, their innocence and their wildness. This has been a time for discerning which aspects of my past I need to let go of, and which I would do well to retrieve and reinstate.

Our separation from the 'more-than human' world David Abram* speaks of has come at incalculable cost. The mechanisms of our achievement-oriented and consumer-driven world have much to answer for; it's as if Humanity's been beset by a kind of psychic virus* that the Covid virus is exposing – at its essence, the dis-ease of separation..

As Gurdjieff once said, “The only way we can get out of jail is to know that we are in it.”

My children’s father used to sing the praises of human bodies as ‘hosts to microbial zoos’ without which we could fulfil neither the most basic, nor the most elevated, of our earthly functions and service.

And did you know that human excrement, when mixed with sawdust—a gift from a lovingly pruned tree—becomes the most nutrient-rich compost for fruit trees and roses?

During this lockdown period, while I feel I haven't ‘accomplished’ much in any outwardly measurable sense, I do feel I’ve been recovering some of the 'innate comprehension' I had as a very young child and that for reasons both valid and invalid, I'd allowed myself to become separated from. I’ve appreciated connecting again with the deep blessing of those early childhood experiences, their innocence and their wildness. This has been a time for discerning which aspects of my past I need to let go of, and which I would do well to retrieve and reinstate.

Our separation from the 'more-than human' world David Abram* speaks of has come at incalculable cost. The mechanisms of our achievement-oriented and consumer-driven world have much to answer for; it's as if Humanity's been beset by a kind of psychic virus* that the Covid virus is exposing – at its essence, the dis-ease of separation..

As Gurdjieff once said, “The only way we can get out of jail is to know that we are in it.”

Our brief time together is drawing to a close. Before we say our goodbyes, I want to say a few words about a Centaur named Chariklo.

Chariklo has only recently come to our attention. She was discovered at Kitt Peak Observatory, Tucson, AZ on 15 February 1997 and has the most spectacular discovery chart – a perfect six-pointed star! We know that new planetary bodies come to our notice in synch with Humanity’s readiness to hear what it is they're wanting to show us.

The Mother of the World is understood to express the principles of the Divine Feminine. My sense of Chariklo is that she is kin of the Madonnas I've shared above and strongly identified with the Mother, a reliable collaborator and force for good. I invite you to read up about her and to see what you think? (Melanie Reinhart* has done a fair bit of research into the centaurs; I recommend her recent essays and talks on Chariklo).

Chariklo has only recently come to our attention. She was discovered at Kitt Peak Observatory, Tucson, AZ on 15 February 1997 and has the most spectacular discovery chart – a perfect six-pointed star! We know that new planetary bodies come to our notice in synch with Humanity’s readiness to hear what it is they're wanting to show us.

The Mother of the World is understood to express the principles of the Divine Feminine. My sense of Chariklo is that she is kin of the Madonnas I've shared above and strongly identified with the Mother, a reliable collaborator and force for good. I invite you to read up about her and to see what you think? (Melanie Reinhart* has done a fair bit of research into the centaurs; I recommend her recent essays and talks on Chariklo).

Chariklo is no push-over! Wife of Chiron, the Wounded Healer, she's a well-equipped mid-wife to crisis. She is also a welcome softening presence during this period when the astrological focus tends to be heavily weighted towards the disruptive forces of Pluto and on the tight Pluto/Saturn conjunctions in Capricorn that we’ll be experiencing throughout (and slightly beyond) this year. Jupiter and Uranus are also in the thick of it and having a field day.

I find it encouraging that feminine Chariklo is right there, in the mix with the 'big boys', and that she will continue to make her supportive presence known as she tracks Pluto and Saturn closely all the way into early 2022. (She is currently at 29 degrees Capricorn).

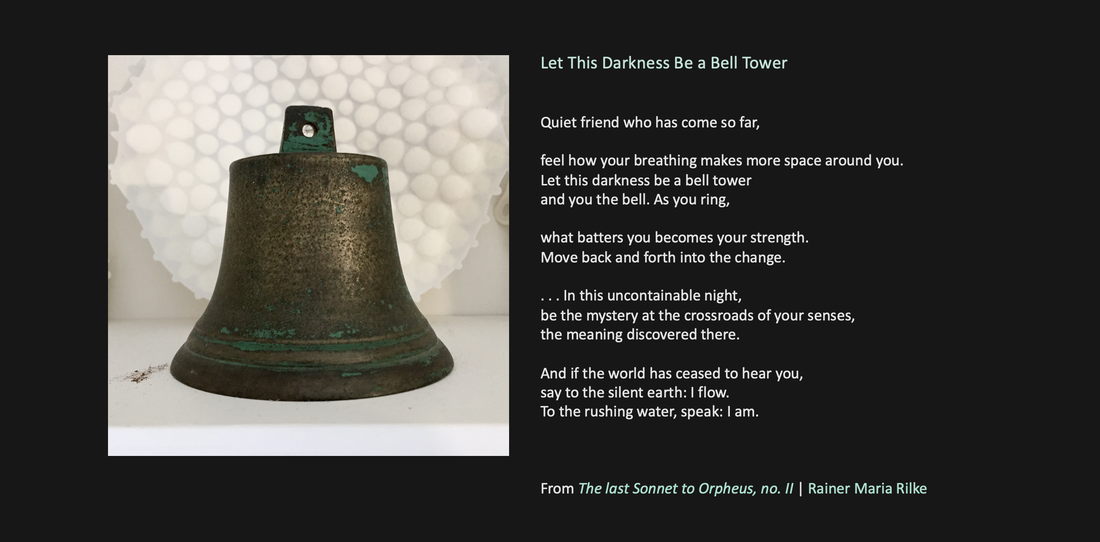

To conclude our time together today, a poem from Rainer Maria Rilke, Let This Darkness Be a Bell Tower (from his Last Sonnet to Orpheus, no ii) --

I find it encouraging that feminine Chariklo is right there, in the mix with the 'big boys', and that she will continue to make her supportive presence known as she tracks Pluto and Saturn closely all the way into early 2022. (She is currently at 29 degrees Capricorn).

To conclude our time together today, a poem from Rainer Maria Rilke, Let This Darkness Be a Bell Tower (from his Last Sonnet to Orpheus, no ii) --

Thank you, friends, for your company.

Let's be sure to keep our fire nests burning, and to remember that what we look at with love looks back at us with love.

CB, Dunedin | May 2020

Let's be sure to keep our fire nests burning, and to remember that what we look at with love looks back at us with love.

CB, Dunedin | May 2020

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS | REFERENCES | RESOURCES

* bayoakomolafe.net/

* Mary Oliver (from her poem, Wild Geese)

* Attributed to Mother Theresa

* philipshepherd.com/

* Paul Laurence Dunbar (from his poem, We Wear the Mask)

* Jane Adams

* Thomas McCarthy (from his poem, The Phenomenology of Stones)

* David Abram

* Paul Levy

* melaniereinhart.com/melanie/index.php

* Miki Kashtan

* Mac Macartney

Whale Image: Tifenn Python

All Other Artworks: Claire Beynon

* Mary Oliver (from her poem, Wild Geese)

* Attributed to Mother Theresa

* philipshepherd.com/

* Paul Laurence Dunbar (from his poem, We Wear the Mask)

* Jane Adams

* Thomas McCarthy (from his poem, The Phenomenology of Stones)

* David Abram

* Paul Levy

* melaniereinhart.com/melanie/index.php

* Miki Kashtan

* Mac Macartney

Whale Image: Tifenn Python

All Other Artworks: Claire Beynon

THE CHILDREN'S FIRE | Heart Song of a People | Mac Macartney

WHEN THE BODY SAYS NO | Exploring the Mind-Body Split | Gabor Mate

"The World-Mother, known by different names in different faiths, is coming forward to take Her special place as the Mother of the World, to be recognized publicly as She has ever been active spiritually. Hers is the tender mercy that presides at the birth of every child, whatever the rank or place of the mother. The sacredness of Motherhood brings Her beside the bed of suffering. Her compassion and Her tenderness, Her all-embracing Motherhood, know no differences of caste, color or rank. All, to Her, are Her children—the tenderest of all human movements and, because the most compassionate, the greatest power in the civilization.

It is a constantly-repeated phrase that every great man had a great mother. But while the great man is admired and honored, she who gave him his physical body is often forgotten, treated with disregard and disrespect. The coming Age is the Age of Motherhood...”

[Annie W. Besant, “The New Annunciation,” The Theosophist, (vol. 49, June 1928), 278.

Image: “The World Mother” by Geoffrey Hodson, illustrated by Ethelwynne M. Quail.]

It is a constantly-repeated phrase that every great man had a great mother. But while the great man is admired and honored, she who gave him his physical body is often forgotten, treated with disregard and disrespect. The coming Age is the Age of Motherhood...”

[Annie W. Besant, “The New Annunciation,” The Theosophist, (vol. 49, June 1928), 278.

Image: “The World Mother” by Geoffrey Hodson, illustrated by Ethelwynne M. Quail.]